GIFT Sikolowe, a father of three, sometimes does not eat for a week – unless he sells one of his wooden spoons for N$50.

Sikolowe takes to the streets of Katima Mulilo daily hoping to sell a spoon so he would have something to share with his children.

“At times, I have to divide that N$50 between me and my three kids, who stay with their mother. If my cousin and his wife don’t help me buy something to eat, I go for days without eating,” he says.

He says he has learnt to ignore the hunger pains.

Sikolowe’s story is not isolated.

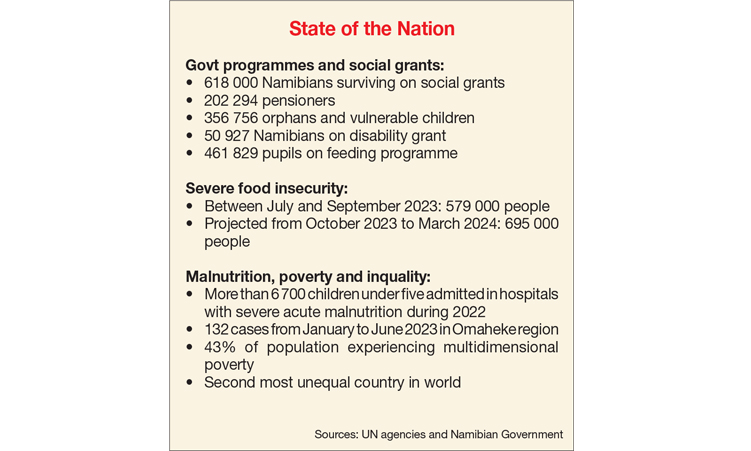

Namibia is facing a starvation crisis with an estimated 600 000 Namibians expected to be food insecure this year.

Between July and September at least 579 000 people in Namibia experienced food insecurity.

Meanwhile, the Office of the Prime Minister is preparing to roll out a N$800-million drought-relief programme which is expected to last until 2024.

“This includes food relief, water provision as well as livestock support,” Hellen Likando, directorate of disaster risk management head, says.

Prime minister Saara Kuugongelwa-Amadhila on Tuesday said the government will roll out the drought-relief programme with food and water assistance in the country’s 14 regions to remedy the situation.

Additionally, it will commence with a livestock support programme from 1 October until March next year.

“[It] entails livestock marketing incentives and subsidies for fodder purchased, as well as leases for grazing, and transportation to grazing areas,” the prime minister said.

This will run at the same time as the government’s safety net programmes, on which 618 000 Namibians are surviving.

These social grants sustain 202 294 pensioners, 356 756 orphans and vulnerable children, and 50 927 Namibians with disabilities.

In the meantime, dozens of families are describing their situation as dire.

The Namibian on Wednesday visited households at Mix informal settlement on the outskirts of Windhoek.

‘EITHER LUNCH OR DINNER’

Members of a family of 12 say they are forced to go to bed on empty stomachs most days, opting to have either lunch or dinner to save on groceries.

The family depends on two pensioners’ old-age grants amounting to N$2 400 a month.

Johanna //Goses (75) says most of her income is spent on the transport cost of her grandchildren who attend school in Windhoek, which amounts to N$700 a month.

//Goses’ husband, Lukas Frits (72), longs for a nutritious meal.

“We drink coffee during the day, and if we eat during the day, we don’t eat in the evening. If we do it means we won’t have lunch the next day,” he says.

Emerita Theofilus (48) says the availability of food is a challenge.

With slim prospects of employment in an economy in which the national joblessness rate stands at 34% and the youth unemployment rate has shot up to 48%, she tries to survive by offering her services as a nanny.

“When there is no relief we can have porridge without meat, fish or chicken, and just stick to soup or rather cook rice that we mix with sugar to add flavour to the meal.

“The day after that takes care of itself,” Theofilus says.

Hileni Ukero (47), the mother of two children, says she cannot keep perishable food as she has no access to electricity.

“I don’t have a refrigerator or electricity. When I don’t have enough money to buy relish, I buy two litres of milk that we can eat with porridge, which we can have for at least three consecutive days,” she says.

In the Zambezi region, several families at Katima Mulilo’s Choto location say running out of food in the middle of the month has forced them into the vicious cycle of borrowing money to buy food.

“My monthly grocery list consists of a 20-kilogramme bag of maize meal, five litres of cooking oil and two kilogrammes of sugar, and nothing else. This is to feed myself, my daughter, and four grandchildren,” Harriet Nyambe says.

“When that happens, we are left for days without eating, and as humans that’s not sustainable – especially not for children,” Nyambe says.

A security guard, Mushowa Maswalo, who also spoke to The Namibian, says she lives with her three biological children and two nieces.

She spends N$800 a month on food, she says.

This, she says, lasts for only two weeks.

“We are dying of hunger. Food prices should be reduced, our children are suffering. You really cannot buy anything for less than N$100 any more.

“I don’t even buy clothes or anything else for me and the children, as any money I get goes to food. I live with constant worry about food,” Maswalo says.

FOOD PRICES SURGING

Over the past decade, some food prices in Namibia have more than doubled.

July alone saw an alarming surge in food prices, with vegetables showing a staggering uptick of 18,1%, bread and cereals escalating by 13,3%, and fruit surging by 13,2%.

The cost of fish followed suit, increasing by 12,6%, while sugar and meat prices climbed by 10,5% and 9,2%, respectively.

Namukolo Sitali says when they do not have food, her children cannot go to school.

“All four my schoolgoing children would miss school for about a week just because we don’t have anything to eat.

“I try to pray for our situation to improve, but at the same time I feel deprived as I’m not enjoying the basic human privilege of having food daily,” she says.

‘HUNGER IS KILLING US’

Olivia Nghishekwa, a single mother of six children from Onekwaya East in northern Namibia, says life is becoming untenable.

“Hunger is killing us. My children go to bed with no little or nothing to eat and it is so sad for a mother to witness,” she says.

Between January and December 2022, over 6 700 children under the age of five were admitted to hospital for acute malnutrition.

Some 132 cases of child malnutrition were reported in the Omaheke region from January to June alone.

HUMAN TRAFFICKING, PROSTITUTION

In the //Kharas region’s Karasburg West constituency, regional councillor Enseline Beukes says the leadership is facing the challenge of curbing human trafficking and prostitution due to hunger and poverty in urban areas.

She says drought-relief food only caters for rural areas.

“We really need the Office of the Prime Minister to review the criteria set for the distribution of drought-relief food to also include urban areas. Urban people have no other safety nets if they are unemployed,” says Beukes.

At the coast, Walvis Bay Rural constituency regional councillor Florian Donatus says the majority of people are relying on the offices of regional councillors to survive.

“And there is no budget for such people. I am using my own funds to buy these people food,” he says.

Independent Patriots for Change national spokesperson Immanuel Nashinge says the Office of the Prime Minister is not proactive in its approach to disaster risk management.

“We can’t afford our own fish! What is the Office of the Prime Minister doing about it?”